From Himal Southasian (1 MARCH, 2012)

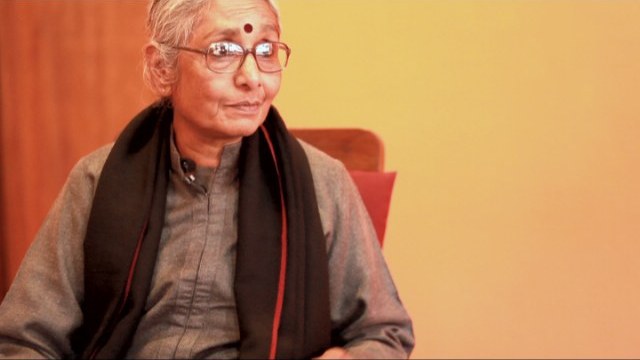

Aruna Roy interviewed by Kanak Mani Dixit.

Kanak Dixit: We have with us Aruna Roy, from Devdungri village in Rajasthan, who has been able to take the Right to Information (RTI) from janasunuwais, or public hearings at the village level, all the way to national legislation that encompasses all of India. It is a movement that is truly global in scale.

Aruna, a question that has been troubling me is that there seems to be progress towards the death of activism. Sometimes because of the whole format of funding, rather than doing something from the heart. Sometimes there can be party affiliations. Development activities have become more a career than a calling. There seems to be an ongoing weakening of activism. How would you respond to that?

Aruna Roy: Well, I know only India very well, and I can’t speak for the rest of the countries. I think there was a lot of confusion in the early 70s when people of my generation began working for issues of poverty, hunger, fighting against injustice at various levels. We didn’t quite realise the impact of funding on one’s actions, particularly if one worked for political action. It was at that time that I really started looking at India’s history. In the growth of the national movement, actually we did have a Gandhi who refused to take office. He did opt out of traditional political structures, but kept what, for want of a better word, I like to call conscious politics, in which you define your ideology and your commitment and your principles, and you speak up for it regardless. You are in the political domain but don’t form part of a party political process. I think that strong process continues to survive in India, despite the fact that all the things you mentioned are happening. It is surviving, and there are many of us now who for the freedom and for the sheer pleasure of being able to say what one thinks is right, will not want to be in any one of these other paradigms. But of course there are other historical reasons why things might be up or down at a particular point of time, but I do think in India things are better. In fact, I would say that in today’s India there is greater clarity, especially in the last two decades, that if you take funding, then your capacities are limited. Because if you want to work within a funding system, even with integrity, then you have to get project funding, reports, you have to do accounts, and you can’t follow the logic of the people to its end. You have to follow the logic of the funding.

Tell us about how the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) fits into the paradigm of political activism that you are promoting.

When we began MKSS, it was decided what not to do. There was very little to decide on what it would do. And I think there my feminist being – I can’t call it a background –and the emphasis on organic processes of participatory leadership and participatory decision-making, on the collective being more important than an individual, had a strong hold on Shankar Singh and Nikhil Dey. They are the colleagues who went with me to Devdungri, they also believed in this. When we began working, we didn’t want to define the nature of this struggle – or the movement or the campaign – without people. So the first three years we just participated in a number of campaigns with people on land, on minimum wages, things which they defined as priorities. Through these struggles the need for an organisation logically emerged. There were more than five dozen meetings held in one year where we debated on the structure, the composition, the decision-making process. And the MKSS then located itself as a political organisation, because we then defined politics not just within the political process of electioneering and parties, but outside of it as fighting within the framework of constitutional rights, and positioning ourselves with the poor, for the poor, the marginalised, the disenfranchised, the minorities, the Dalits, the women.

So what makes MKSS political?

The political is in how you see an issue. The same issue can be seen in ten different ways. RTI, for instance, can be just a seminar done by academics, it can be a workshop done by people funded to spread the word, spread awareness about RTI. It can be the struggle of an individual fighting for his or her rights with the state, with a government office. It can be a poor person fighting the denial of rights, the denial of life and liberty. It can be the fight of a large collective on issues. So we would then not be party to the first couple mentioned but we would be part of the latter bit, where RTI would be seen as part of a democratic struggle, to see that there was both no arbitrary use of power and no corruption, that the system delivers as per its obligation to the people. So it becomes a political act.

And that requires organising. That is also what makes it political – that it is a group, acting for a goal, even if it is not through a party.

Even an individual, independently working, must understand that it is not just merely settling of a corruption issue, but by asking those questions they actually ask questions of the state or the government which have larger implications.

Why did you settle on RTI as your entry point?

The thing is that it has evolved. That is why I made that first statement about feminism, because a movement has to evolve from a group process and thought, it can’t just come from anywhere. Many of us felt that secrecy was terrible – we have something called the Official Secrets Act in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, wherever the British ruled. They’ve left that great gift to us, the Official Secrets Act. So every time you asked for information from the government you came up against this block. So we were all aware that that Act needed to be set aside in order for more transparency. In fact the VP Singh government had tried to enact a RTI law. So there is a history.

-

But what actually sharpened this was the struggle for minimum wages that MKSS was organising and fighting in rural Rajasthan. Time and again, people were told that they were liars, and the official records became terribly important both to prove their integrity, and to get a right to a livelihood, or a right to a wage, which meant food, which meant staving off hunger, which meant living a reasonable life. So at that point it became a critical issue.

But the definition of the movement actually came from many people. I’d like to refer to Sushila here. Sushila really defined it in 1996 after a forty day strike – a sit-down strike in Bijabar. We had formed the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information. We went to Delhi for a press conference, and Sushila was asked, ‘What are you doing here? You’ve only passed your fourth class, you don’t know anything about academics. It’s a big intellectual question. We’re talking about freedom of expression and Article 19 of the Indian Constitution.’ But she said to them, ‘Look, when I send my son with 10 rupees to the market place, when he comes back I ask for accounts. The government spends billions of rupees in my name. Shouldn’t I ask for my accounts?’ And she said in Hindi, ‘Hamara paisa, hamara hisab.’ So she said, ‘It’s our money, our accounts.’

So it is the simple, common-sense logic that actually defined the Right to Information movement. Then it acquired all the other various layers of the legislation, and an understanding which spread further, which spread to every aspect of governance. Today, RTI is one of the best used laws in India. But it grew from a common-sense perception of peoplehood.

If I may just add one favourite quotation of mine these days, Eduardo Galeano – one of the greatest political thinkers of South America and the world – says that nothing goes from top to bottom, except for the drilling of holes. He says that everything else, by the very meaning of the term ‘grows’, grows from the bottom up. So I think RTI has come to stay, because it is being developed and fashioned – the dos and don’ts, and the non-negotiables have been defined – by people who suffer the most from arbitrary governance.

What is the spread of RTI around the country now, and what are the challenges being faced? Because I would expect it’s not enough to have legislation, you’ve got to watchdog it, to make sure that it does what it is meant to do.

Actually I was quite amazed that it has spread to all sorts of sectors. It is being used by the people who are the most oppressed. I would not say it has spread all over India. There is a sufficient number of groups all over India who use it, but the groups I’m talking about are the people who are most oppressed. So it’s the Dalits who use it in cases of atrocities against them, you have the poor using it to access food and shelter, you have minorities using it for access to their rights, as in Gujarat, where people who were victims of the genocide have recently used RTI. Recently I have been in Manipur, and even though there is an Armed Forces Special Powers Act which restricts everything, the women who are ‘gun widows’ use RTI for accessing their minimum needs. Nobody knows us, no one knows the MKSS, no one knows Aruna Roy or Nikhil Dey or Shankar Singh. But the joy that I get is in seeing RTI being used more logically by the poor.But there are some untoward and sad incidents. We’ve lost about 15 activists who have been killed in the process of accessing information. They had access to sensitive information. There are many of them, single people – in the sense that they are not working in groups – and therefore they have been identified and killed. Now we are fighting for some kind of protection for those activists, either through an extension of the Whistle-Blowers Act, or some kind of protection that will cover their issues. But it is a huge problem. This also proves that using RTI is a political act, since no innocent act of just asking for information would lead to this.

I would just like to add one little incident which has come to my mind. You know the Bombay terror attack, and we lost three important policemen. One of the widows of those very eminent policemen – who was given a martyr’s funeral – she couldn’t access the post-mortem report from the police station, even with her husband being a policeman, except through RTI.

Would you say that the RTI Act has the possibility of seeping to the capillaries so that it covers accountability at the national level, but also accountability at the village level?

I like that phrase. Yes it has seeped to the capillaries. My nephew went trekking in the Himalayas, and went to Lahaul and Spiti, and saw that there was a community of villages which had one person who was an RTI facilitator, who helped them write applications. So RTI has already reached those places.So soon enough you may not even know all that is happening in this area?

I simply do not know, and I have not known for the last four years, where all it has spread. Though, there are huge issues. One is that the mandated information commissions are not looking after their responsibilities. The government has not implemented Section 4 of the Act, which requires it to proactively display information. It hasn’t fulfilled its obligations at the central government or the state government level. Almost every single government office has not done it. Just a few have. The websites are not in place except for some, like the Ministry of Rural Development, which has done it. But there are others who haven’t. There are public information officers, who are very adamant and don’t provide the information, and have harassed people. -

Are there some states that are better than others?

Well, I think there are different sets of problems in every single state. I don’t think there is any one state that has done phenomenally. Except if we look at NREGA’s (National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) work, where there is a part of it which is related to the Right to Information, which requires displaying information and auditing it publicly. That I think the state of Andhra Pradesh has done very well. But if you look at public display of information they are poor, if you look at RTI they are very poor, there are commissioners who have been appointed without transparency so there is an agitation in Hyderabad, so it’s a mixed bag.Is this not something that will require constant watch-dogging?

See, I think every single thing, including democracy, actually needs constant watchdogging. I think the power of the vote is not just to cast it once in five years as we do in India. I think the power of the vote also gives you an obligation along with the power, and that is to monitor the way my government runs for me. What RTI does is facilitate that obligation. And actually when the RTI Act was passed, I thought, ‘Aaah, now I can relax.’ But after that, work has quadrupled, because in the use of the act there are more problems than in the making of it.Once you have started on this path of political activism from the bottom up to change the face of Indian society, there are these other areas that you’ve also now got engaged in. One of them is the right to work, one of them is right to employment, one of them is the right against corruption. Do you find yourself now engaging in other areas because it is the next step after RTI?

Actually RTI by itself is nothing. RTI must be applied to a set of activities, within a certain panorama, within a certain sector. And you know the English said the devil lies in the details, and so it does. Every single question of the RTI Act unravels another huge set of challenges. So it requires a particular kind of tenacity and purpose, and a detailed understanding of how things function. That is when you know where the nerve centre lies, and then RTI becomes an absolutely invaluable tool.RTI is actually a seminal tool for democracy, and what it does is help in the sharing of power. And it shares power in a manner in which it doesn’t matter where you are located and whom you are talking to. Because this power is rightfully that of the sovereign, the people of the country, which is vested in a system to govern, whether it is politics or bureaucracy. Then it is understood that you are actually only a caretaker of what is the power of the people. And I also don’t agree that people can run in anarchy. You need a government, you need a political party which will state its ideology and work according to this ideology, but that also needs to be monitored. Even parties which have a very good ideology can go astray. And the bureaucracy, of course, can be spineless and go whichever way it is pushed in order to maintain the status quo.

So in that sense RTI could help stabilise democracy and make it real. We talk about elections not being all that democracy is, so what is missing seems to be this element.

Yes, it is a very important way of looking at a revolution, bringing in equality, which our constitution has given us on paper since 1951, so to get that equality in place, and to also fight against the symptoms of mal-administration and governance. That is why in India now, interest in governance has become a revolutionary thing. Actually it would have been dismissed 30 or 40 years ago as rubbish. It was more about telling those interested in governance that [they] should look at changing the political party. But we found in India that you keep changing your political parties, and their stated agendas are very different, but in actual fact nothing really changes. So how do you make the real changes happen? That is where RTI has really located itself – in democracy. It derives from constitutional right and therefore it is constitutional. It looks at parliamentary systems, it looks at the role of the Parliament. The law was enacted in Parliament, it was dialogued with political parties, so the political parties looked at their agendas and their manifestos. It brought in the notion of accountability, because if you make a promise you must keep to it. Then it is our obligation – the activists obligation, the people’s obligation – to make sure that accountability exists. So RTI brings in the plurality of democratic structures, and of no one group or one entity being paramount in it.What about accountability in India at the national level? Can RTI reach those rarefied elevations as well, to demand accountability when multi-billion dollar scams occur?

Actually it has. You see, RTI is not a political movement. The RTI is a tool. So what does it do? It unearths information which would otherwise not be accessible up front. Many of the battles that have been fought have been fought because of RTI applications made to access that information. Then you have to fight a political battle. See, in the political battles, I think the poor fight longer and in a more sustained manner than anybody else. So the battles of the poor have been sustained over years.Whereas the battles of the big scams have to be fought by the middle class and the upper class elite. Because it is a battle in which the idiom is so different today, because payoffs are not in sacks of money that are unearthed from under the floor, but they are in deals, and so on and so forth. That awareness has also come now, and that is why we argue that you need a different structural system to fight big-level corruption than to fight poor people’s corruption. Hence the understanding that a plurality of groups need to align themselves to fight corruption. You can’t have one group fighting all systems.

-

If it is the middle class and the professional classes who also have to be alert, is that what the Lokpal Bill is all about?

Actually, the campaign began with the definition of an angst which preoccupied India for years. Ever since I was young corruption has been a topic, always talked about at home, and at the dukaan. The Lokpal Bill as present actually would lead to an extraordinarily empowered bureaucratic system – another vertical structure and another policeman, in very simple terms. The system put in place by the Bill would inevitably become corrupt, from our point of view, because power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. So if you create a bureaucracy which oversees all wings of government – the judiciary, the legislature, and the executive – then within that institution, who polices the policeman? It is a big issue.But the Lokpal Bill was supposed to police the policeman.

But then it becomes another policeman. So who polices that policeman? Accountability has to be there at all levels. So for our part, we offered a formulation which is now being broadly accepted by many people.Tell us about that.

In that formulation, we’ve broken it up into its logical components – not too big – so that each can oversee the other and there is some amount of accountability. So one would be the high-level corruption; that was the bill that went into a morass in the Rajya Sabha, with nothing resolved. Then there is the Grievance Requests Bill, which is now with a standing committee of Parliament. Then you have the judicial accountability, you have judges like Justice Verma who argue that the judiciary must be independent, and if you take away its independence then you take away one of the most important over-seeing mechanisms in a democracy. So now you have the judiciary with its own standards of oversight. But most important of these are the grievance requests at the grassroots, which have now become the most important aspect that will concern millions of Indians.Please tell us more about the grievance request activism.

Well, let me just tell you a story. I think stories can be the most telling. This was about 6 weeks ago, maybe 8 weeks ago, in a small town called Bhil in Rajasthan. We had a public hearing and a grievance request meeting on electricity with people who had grievances with the Electricity Department. We invited the collector, who is the biggest administrator. With him came all the officials, and we had people come and say what was wrong with their electricity systems. This need not be corruption, may be corruption. And what happened? You have a meter, which is not connected to anything, but it is still telling you that you have to pay money. You don’t have a bulb. You’re supposed to be given a free CFL bulb, but there is no CFL bulb. There is nothing, but you’re still being billed. And then when you want the electricity, you are being told that the pole can’t come to your village home because it requires a special amount of wires to be put in. You’re a Dalit, you enjoy certain benefits, those benefits have not been given to you. So over 500 people came to that meeting. Amazing results, because all of this had already been sanctioned on paper. Within the next month, there were 4000 homes where people were provided CFL bulbs. Otherwise they would have been pocketed, and that was 40 lakhs worth of CFL bulbs, in Indian rupees. The point is the complainants didn’t want a criminal case against the Electricity Department. The people with grievances just want a light to burn that day, to cook, to read, for the children to study for their exams.Grievances are such things. So it could be a hospital, it could be electricity, it could be a ration card, where I don’t have a ration card and I need food tomorrow. I am not interested in the criminality of it, but I the service, I want my ration card. So it involves a separate set of things. If there is a criminal action, that can be taken up with the police station or with the Lokpal, whichever category it comes under. But for the grievance, it must be addressed immediately.

So rather than bring a criminal case, I just seek the service. But where is the sanctioning power behind this bill?

We have looked at an entire system that will be created, which will not be a new bureaucracy. Look at the RTI Bill. It has not created another bureaucracy. What we have done is empowered certain people within the system to act as information officers. There will be grievance request officers, who will be given a time limit, and within the time limit they must settle the issue that is brought up by the citizen. If they don’t, like in RTI there will be a penalty levied on them, and the penalty is the trigger that makes people work. Then there will be an appellate system, and there will be an appellate authority at the district level to deal with it, but it will be time bound. If it’s not time bound, then it’s pretty useless.So there is now the possibility of a Greivances Addressed Act coming from a Grievances Addressed Bill, which you are helping to fine-tune and polish. And that is a national-level act?

Yes, it will be a national-level act, and the debate is on as to whether under the Indian federal structure it can be applied to all the states. We are arguing that if the RTI Act could be an act that applied to the whole county, why not grievance requests. Now it is under debate, let us see where it leads.So from Rajasthan and Devdungri, from RTI and its country-wide application, you’ve now moved on to grievances. Where else do you think you will be led to?

I think the MKSS has a lot of things to do. Personally, I think I should look at what I can do as a retired Indian. -

But how does one retire when one is an activist?

I think one takes on different jobs.I want to end with a personal question. How would Mohandas Karmachand Gandhi have taken to MKSS, in your personal estimation?

I think Gandhiji would have approved of some of our things, and been a little sceptical, maybe, of some of the things we do. I have lived with Gandhiji in my mind since I was born. For me he has never been away from my psyche. But I have also thought about some of these things. So I suppose he would have absolutely approved of the way we live, he would have approved of the way we struggle, he would have approved of our primary identity with the very poor, he would even have approved of the biases that we have in our politics, but he may have had questions about how much you can trust the government with leading the right way. But somewhere there I think one has to come to an uneasy compromise even with one’s instincts, because much as we may dislike governments, governments are necessary to govern countries. We believe in nation states. And political parties are necessary for parliamentary democracy. And for people, poor people, parliamentary democracy is vitally important. We may have had a few quarrels with Gandhiji on that, but still I think we would have largely got on.And I think Gandhiji may have approved of the fact that MKSS functions, even till today, out of a small hut in Devdungri—

And with no institutional funds.

And with no institutional funds, he would have liked that too.

~ Aruna Roy is an Indian social activist, the founder of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan, and a prominent leader of the Right to Information movement.

~ Kanak Mani Dixit is the editor of Himal Southasian.