From Himal Southasian, Volume 22, Number 10/11 (OCT/NOV 2009)

The sputtering row over the ‘Indian’ priests of Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu has its origins in the xenophobia that evolved as part of the hill-centric Nepali nationalist psyche, a mindset that is used by modern-day demagogues to garner easy popularity and support. Since before the time of Nepal’s unifier, Prithvi Narayan Shah, two and a half centuries ago, the hill principalities have been wary of ‘Mughlan’, or the plains-land of the Mughals. Kathmandu Valley’s rich mini-kingdoms, in particular, harboured deep antipathies against the powerful nawabs and rajas of the south. One mythical story from Patan town refers to how a local tantric named Gaibhajya overcame a tantric from Mughlan. This besting of ‘India’ is recounted with glee to this day.

At the dawn of Nepal’s modern era in the mid-20th century, King Mahendra stoked this historical xenophobia in order to consolidate his own authoritarian grip. With the emerging power of modern India, the historical ultra-nationalism coagulated into anti-Indianism. The fallen democrats, led by Bisweshwor Prasad Koirala, were all termed arastriya tatwa (anti-nationals), a synonym for ‘Indian lackey’. Two full generations of the Panchayat era were groomed as xenophobes, even as those in power in Kathmandu knew they had no choice but to secretly supplicate before the Delhi Durbar.

The Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) essentially incorporated Mahendra’s ultra-nationalism as a plank and platform by which to raise populist support. The Pashupatinath episode is the result of this simplistic head-in-sand chauvinism that has been fed to the Maobaadi cadre, with its uni-dimensional view of Nepal’s history. Meanwhile, the Maoist leadership is simultaneously loudly anti-Indian in public and sycophantic towards New Delhi in private.

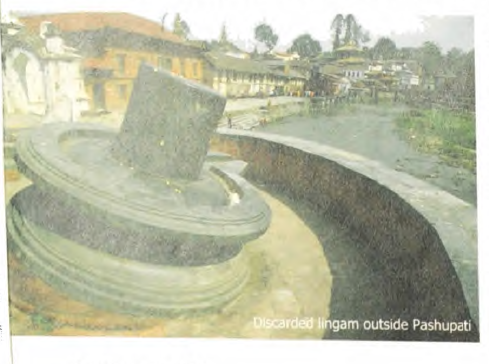

Pashupatinath’s origins go back to pre-history as a peeth, or power place, dedicated to the ‘lord of the beasts’, at the outskirts of ancient Kathmandu by the Bagmati River. As it evolved into a temple dedicated to Shiva, from the Lichhavi period till the 16th century sansyasis from the plains are said to have come to serve as priests. In the mid-1700s, the tradition began of bringing the mool bhatta, or head abbot, from south of the Vindhyas. It continues to this day, interestingly mirrored in many priests of hill Nepali origin serving in their thousands in power places of India today.

The sourcing of abbots from afar seems to be linked to the need for temple administration to be free of ‘localisation’. This protected the deity from ritual pollution, and kept outside the push and pull of local politics. The system of transporting a bhatta all the way from south of the Vindhyas was also perhaps because the Kathmandu nobility believed the pandits of the northern Subcontinent to have been sullied by ‘infidel influence’.

Some may have thought that the atheistic Maoists would have left matters of religion alone. But their irreverence for faith was supplemented by ultra-nationalism of the modern kind. A clash on the precincts of Pashupatinath was perhaps inevitable; and because they were leading the government, it was a small step for the Maoists last year to try and shake up the appointment process of the Pashupatinath abbot. For them, the diktats of nationalism required the ouster of the two ‘Indian’ priests of Pashupatinath, to be replaced with Bahuns (Brahmins) who were Nepali citizens.

The Maoist leaders obviously did not appreciate the level of disquiet they would create among the Shaivite faithful, within Nepal and far beyond in the Hindu realm. Besides carrying out an act that would be a hurdle in their path to post-‘revolution’ gentrification, the Maoists were also putting their fingers into a geo-religio-political cauldron where they were sure to be scalded.

Here was an immature attempt to put the stamp of modern-day nationalism on a matter of faith that went back to the time before the Nepali nation state, and long before competitive nation-statism arrived in the Subcontinent in the mid-20th century. After all, against the historical prism, this could hardly be considered a matter of ‘Indian’ priests at Pashupatinath, but rather the appointment of ‘Krishna Yajurvedia, Dakshinatya Tailing Brahmans’ from Karnataka to serve Lord Pashupatinath in Kathmandu Valley. In fact, what we have is an interaction between two cultures of the extreme north and deep south of the Subcontinent, and which – if the modern-day chauvinist nationalist argument were needed – proved the sophisticated civilisation and Southasia-wide power and reach of Kathmandu Valley going back more than two centuries.

Much must change at the Pashupatinath Temple. There is massive diversion of the ritual gifts of devotees, and none of the transparency seen at, say, Tirupati. And it is not that there can never be changes in the system of appointment of priests to mind the ‘lord of the beasts’. Sage scholars of religion in Kathmandu argue that Nepali citizens can indeed be inducted, given the proper mindset, Vedic training and ‘Krishna Yajurvedia’ tradition.

But, I argue, why not maintain a tradition that is Kathmandu Valley’s and Nepal’s link to Southasian history? Pashupatinath must be converted to a temple worthy of the modern era, with clean precincts, open admission, and managed by a trust that is transparent and involved in good works. Let the priests be paid salaries rather than being ‘on the take’. But let us think twice before breaking this historical cultural tie that binds the far north and far south of Southasia.