From HIMAL, Volume 0, Issue 0 (May 1987)

Pollution in Kathmandu

Reported by Praksash Khanal and Anil Chitrakar and written by Kanak Mani Dixit

Except perhaps some centuries ago, when town planners under the Mallas still had their say, the three urban centres of Kathmandu Valley have always been dirty. Stagnant sewers, mounds of solid wastes, open-air latrines and drinking water swarming with bacteria have always been a part of the Kathmandu, Patan and Bhaktapur ecosystem.

While things have been slowly worsening further since the turn of the century, during the past decade the Valley has slipped into an environmental tail-spin. The situation has become desperate as air, water, solid-wastes, and even air pollution choke the three town cores as well as the urban sprawl neighbourhoods. This deterioration has been fueled by the Valley-centric development of the country, a near-total absence of planned expansion, a tripling in the number of poorly-maintained motor vehicles, the only cement factory in the world located four kilometres from a city center, a micro-climate that tends to retain atmospheric pollutants, the lack of pollution standards, and a largely pliant academic and journalistic community that does not demand enough.

Surprisingly, there have been no official studies commissioned to check how bad the quality of environmental life actually become for the hundred of thousands of Valley residents. Neither the Department of Meteorology nor Tribhuvan University keeps a simple device that can measure air quality and there are not even facilities for rudimentary samplings of effluents and ambient air and water. In 1983, officials at the Royal Drugs Research Laboratory even refused to test the water from the Dhobi Khola rivulet for fear that their equipment would be damaged by the heavily polluted samples.

While funded studies are lacking, however, there is no dearth of professionals: doctors, scientists and others who are concerned and have kept track of the decline. Even lay observers have noticed that there is more haze over Kathmandu every year. “What can you say of a situation where fecal matter comes out of water taps, as it did in Samakushi (a Kathmandu neighbourhood)?” asks Dr, Damodar Upadhaya, Chief of the Health Ministry’s Epidemiology Divisions. According to Upendra Man Malla, the member of the newly reconstituted National Planning Commission responsible for environment and coriservation matters, when he goes up Nagarkot hill these days and looks down at the brown blanket of smog over the capital city, he feels, “kay bhayeko jasto lagchha (what has happened)!”

“After eleven years away from Kathmandu, I find the city unrecognisable,” says Nara Oja, who now lives and works in Hawaii and is visiting with his wife Marietta, “It used to be when the winter fog lifted you could see the Himalaya to the north.”

“Now I can barely make out the surrounding hills.” The Ojhas’ concerns are a daily worry for Kathmandu’s hotel

owners, who have begun to notice tourists are loathe to tarry around in Kathmandu if they can help it.”It’s true, we wish we had trekked a few days longer and left Kathmandu for the middle of the monsoon,” says Londoner.

Christine-Anne Horton, who with her husband, Donald Hirsch, suffered from raw throats and sinuses while bicycling Kathmandu streets through dust and dies el smoke.

A vanishing ecosystem

Godavari, 15km southeast of Patan, today represents in a microcosm the ecological degradation and mindless “development” that is going on in the rest of the Himalaya. It’s all there – a balding hill, slopes clawed by the red scars of landslides, springs going dry, vanishing birds and mammals, charcoal traders committing arson on the ridges, quarrying that has opened a gaping wound at the base of the mountain, shantytowns of workers and their families where rhododendrons once bloomed.

An edict by the Rana rulers of Kathmandu kept most of Godavari’s forest intact for the past centuries. Anyone found felling a tree here, the rule said, would be beheaded on the tree’s stump, Later Rana prime ministers built summer resorts inside Godavari’s jungles. The steep ridges were blanketed in’ oak and rhododendron forests interspersed with lush groves of bamboo and pine – a floral mix allowed by the differing climatic zones on the more than 4,000 feet of. altitude variation.

Godavari, this valley within the valley, has now become a prime spot for the newly-emerging environmental groups in Kathmandu to see ecological destruction taking place “live”, The Nepal Forum of Environmental Journalists recently took itself on a day’s outing to Godavari and the place is regularly visited by delegates attending various environmental conferences in Kathmandu.

And amidst all this spectacular destruction, foreign heads of state visiting Nepal roll through in motorcades to ceremonially plant trees at the Royal Botanical Gardens. Meanwhile, Godavari resounds with the sounds of war – deep booms of dynamite rent the air as oblivious urban picnicers sing drunken songs in the artificially symmetrical gardens. It rains rocks at a nearby high school when the dynamites go off at the increasingly mechanised marble quarry.

“Godavari is getting warmer, tropical butterflies are migrating up from the Terai,” says Mahendra Limbu, an avid butterfly collector at the school.

Even trees near Phulchoki’s summit are not spared, A recent visit there revealed giant oaks being cropped for fodder by women who had trekked five hours to get at the choice leaves. On the western ridges on the Lele side, whole hillsides have been charred by charcoal pickers. And the ubiquitous goats are there to nibble off the tiny green shoots that have sprouted from the ashes.

(Prakash Khanal)

Fertile floor

Kathmandu Valley covers an area of 597 sq km and is unusual for its size and nature. A fertile floor and an entrepot nature made it the foremost urban centre in the Himalaya, and even today it has the largest population concentration in the region. Its old towns show sophistication in planning, with sewer systems, community waterspouts and streets paved with granite slabs polished by the soles of ages. Urban clusters were concentrated fields and vegetable patches. “Modernity” has changed all that. The old community based waste disposal system has collapsed and the demands of the swelling population has far outripped the ability of the ancient infrastructures to cope. “The first impression of foreigners is that Nepal is beautiful but so dirty. Kathmandu gives the whole country a bad name,” says a United Nations official stationed here.

Half of the Valley’s present population of about 800,000 lives in the three towns and the other half is divided among 100 villages. In the city core, the population density is as high as 1,200 persons per hectare. Between 1954 and 1981, “Greater Kathmandu” (comprising only Kathmandu and Patan. Bhaktapur is a distance.) tripled in size, according to a urban land policy study completed last April. It says that in the absence of land use regulations, the urban growth has been very haphazard. Even if land use regulations were enacted, however, the enforcement problems would be “formidable”, the report states.

Greater Kathmandu is the only city, its size which does not have a major river flowing through it, an ironic situation for a country with huge snow and monsoon-fed rivers such as the Kosi, Gandaki and Karnali. The Bagmati watercourse, with a mountain spring as its source barely 25 kilometres upstream from the city, becomes a mere rivulet in winter and has lately taken on the characteristics of a sewer. Especially in the dry season, wastes never get flushed out of the city. A Southeast Asian travel magazine put it rather viciously when it called the- Valley “the toilet bowl of Asia”. Taking each of kind of pollution separately – solid wastes, water and air – and even being a proud resident of ”Nepal khaldo”, one could agree that the magazine was not far from the truth.

Talking statistics, the Valley produces 138 tons of solid wastes a day, of which 70 tons are carted away by the West German aided Solid Waste Management Committee to a dump at Teku. Organic waste is processed to make fertiliser, which is in high demand. Metal and glass wastes are sold to middlemen for recycling in India, says D. B. Rayamajhi, Chairman of the Committee. About 21 tons of wastes are picked up by the three Town Panchayats, who hire more than 1000 sweepers, many of whom still use buffalo-rib scoops – “appropriate technology” — to pick up refuse. The remaining 48 tons of daily waste do not get picked, until piles get so high that it becomes an embarrassment to the city fathers and mothers, or HMG.

.. meanwhile in other Himalayan valleys

The pollution of Kafhmandu Valley is not an isolated phenomenon. Other valleys and other towns throughout the Himalayan chain are already suffering heavily from environmental dislocation or will be.soon unless corrective action is taken. Shimla recently had a water quality scandal, and the deterioration of Darjeeling town has proceeded unchecked for more than a decade. In Srinagar, planners are worried over the preservation of Dal Lake, while further west in the Peshawar Valley, too, the problems of water supply, sanitation and health are keenly felt. Even Thimpu, with a population of only 15,000, has begun to suffer from inadequate water supply and sanitation systems, complex and narrow road networks and inappropriate land use. In Lhasa, authorities are already gearing up to cope with increased pollution as an open door policy brings more economic opportunities to the town.

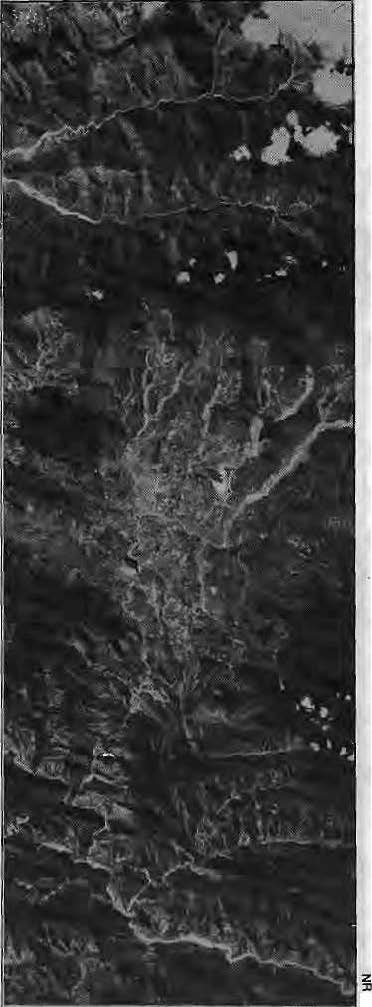

The highly urbanised Doon Valley of Uttar Pradesh, with Dehra Dun as its hub, has many problems that are identical to Kathmandu’s. The concentration of population and consequent urbanisation have led to deforestation, soil erosion, siltation and air pollution. LANDSAT satellite imagery has shown a twenty percent reduction in the forest cover between 1972 and 1982.

There are six factories that depend on mining operations, but the primary pollutant is the ARC Cement Factory near Rajpur, in operation since 1981 The Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board had apparently issued ARC a “no-objection certificate” back in 1981. With public protests becoming more strident, the Board withdrew its certificate. Despite that, it is reported that the district administration did not have the regulatory muscle to order the plant closed.

Last year, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi asked Chief Minister Vir Bahadur Singh why polluting industries in Doon had not been closed and why, instead, the state had commissioned its own calcium carbide plant. Following that communication, the ARC factory, among others, was ordered closed. Stormy protests followed and industrialists and lime kiln owners combined forces to form a committee to argue about implication for employment and income.

Mady Martyn, Chief Coordinator of the conservation -minded Friends of Doon, says her group is not for overnight and forcible shifting of the industries and lime kilns. Alternate sites outside the valley must be made available and measures taken to mitigate unemployment, she says.

Last fall, the Doon Valley Board, at a high-powered meeting chaired by the Centra) Minister of State for environment and Forests, recommended that the Valley be declared a pollution-free zone in which “only non-polluting industries like electronics, watch-making and assembly of instruments should be permitted”. To protect Doon’s fragile ecosystem, it called for concessions and subsidy to non-polluting industries and recommened that industries which did not make intensive use of water and power be encouraged. The Board also demanded that lime kilns be shifted from the Valley and that pending applications by pollution prone industries be rejected out of hand. Finally, the Board proposed the preparation of a land-use master plan for the Doon Valley region after consultation with representatives of the public.

Rotting corpses

Water pollution in the Valley is primarily a result of the inability of the existing rivers to carry away and dilute organic and toxic wastes. Untreated sewage is directly released into the Bagmati and its primary tributary, the Btshnumati. Solid wastes are dumped by the riverside. The ashes of the departed, and the rotting corpses of dead dogs, wastes of slaughter houses all meet at the river. This is the same water – “fluid” might be a better description – that is used to wash most of the vegetable sold in Kathmandu markets. “The water is okay, I just have to get this mud off the radishes and have them clean,” says Astamaya Maharjan, stopping by at the Bishnumati bank on her way to the Ranamukteswar market. She works in the early morning mist, but this is also where clothes will be washed and kids will frolic and get bathed later in the day.

Aehyut Sharma, Accociate Professor of Microbiology at Tribhuvan University, says the World Health Organisation recommends rejection of water that has even one colony of E. Coli bacteria in one ml of water. Studies in Kathmandu have found up to 4,800 colonies of bacteria per ml. Comparing notes from research he did in 1978 and in 1985, Sharrna says he found the water quality in Kathmandu going from bad to worse.

The poorer segment of the inner city population use open toilets, out by the ponds and rivulets. Even in newer neighbourhoods, toilet outflow lets out directly into the shallow drains, whence it often bubbles out into the street. Sewer and water pipes often run scandalously side by side. Kathmandu’s intermittent water supply creates suctions in the pipe so that pure untreated bathroom waste gets sucked directly into kitchen tap water. “In such a situation, you have infective hepatitis, dysentry,typhoid and every water-bome disease in the text book,” says Upadhaya.

While surface water might be polluted beyond recognition, the purity of groundwater is also of concern because of the large numbers of spring fed community waterspouts in the city cores. While, again, detailed studies are lacking, Sharma says that the proliferation of septic tanks (dug because there is no sewerage) in the thousands of new houses built annually have an adverse effect on ground water. Industry is also to blame, he says, citing as an example the Jawalakhel Distillery in Patan, which has “destroyed the water at Dhobi Ghat”.

Sharma says the Bansbari Leather and Shoe Factory’s untreated discharge of toxic sulphide and chromimum compounds into the Dhobi Khola has destroyed the ecosystem of that rivulet, which flows right through the centre of Kathmandu town. Often, the effluents do not even reach Dhobi Khola because it is channeled by local farmers for irrigation. Those coming in contact with these wastes are in danger of contracting anthrax, which can lead to lesions of the lungs. The leather factory presently soaks about 400 cattle and buffalo hides per day, 40 percent of which goes as solid or liquid waste. Ajit Thapa, Bansbari’s General Manager, says the factory is aware of the problem of pollution and is contemplating primary treatment measures.

While solid wastes and water pollution have had a long history of bringing filth and disease to the lives of Kathmandu residents, it is only in more recent times that air pollution has made its presence felt. Especially during calm winter days, Greater Kathmandu has air quality that international travelers compare to Tokyo and Los Angeles. The otherwise idyllic setting, on a wide bowl-shaped vailey in the lap of the Himalaya, aggravates the problem. In winter, a layer of warm city air is trapped under a higher layer of cold air flowing down from the mountains. This “temperature inversion” causes smog to blanket the city all night and for most of the morning. “Kathmandu’s micro-climate is such that air pollutants tend to settle down rather than get blown away,” says Suresh Chalisey, a meteorologist and former Member- Secretary of the Man and Biosphere (MAB) Nepal Committee.

Kathmandu smog has become a major health hazard, says Dr. Sanjiv Dhungel, a cardiologist and Associate Professor at the Teaching Hospital. He says the percentage of patients suffering from respiratory diseases and bronchitis caused by city pollution is high, but points out that the major problem even in Kathmandu is still “indoor pollution”, caused by wood-burning in closed spaces.

Another doctor at the Teaching Hospital, Subodh Pokhrel, says that even with increasing access to medical facilities, antibiotics and well trained practitioners, the incidence of lung diseases in the Valley is on the rise. He ascribes this trend to the growing air pollution, which weakens the lungs and leads to chronic diseases. He warns that “the worse is yet to come, for these pollutants will settle in different parts of the body and might ultimately give rise to carcinogenic cells, which will lead to an increase in cancer cases”.

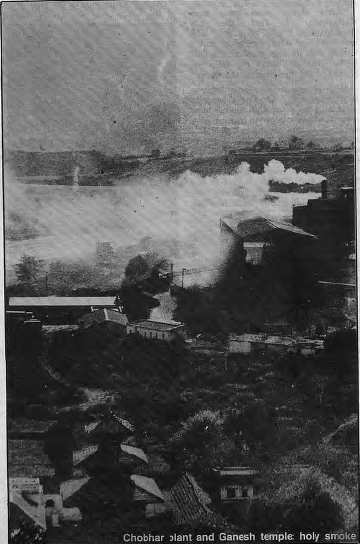

The chief whipping-boy of the capital city’s “cocktail environmentalist circle” is the Himal Cement Factory at Chobar, near the gorge where the Bagmati exits the Valley. Commissioned in 1974, the factory is riding the crest of the construction boom in the capital, providing 48,000 tons of Portland Cement yearly. At that rate, the factory can continue to produce and to pollute for another hundred years before the limestone deposits in Chobar run out. According to a 1983 report by the Forest Services group, Himal Cement’s two vertical shaft kilns and a rotary Jdln together produce five to six tons of dust .every 24 hours. It claims that no direct stack sampling is carried out for measurement of emissions and that there is no systematic monitoring of dustfall in the area. The technology for controlling emissions, including electrostatic precipitators, can be retro-fitted into the plant, the report maintains. It says that supervisory personnel in the plant were unwilling to provide information about existing installations, “but evidence of continuing excessive emissions indicates chronic malfunctioning of abatement equipment, if any”.

Indu Bahadur Shahi, the factory’s Chairman and General Manager, told HIMAL that electrostatic precipitators are not appropriate for vertical shaft and kiln chimneys. However, he says, government approval has just been received for installation of ‘wet scrubbers’, with West German assistance, which -should reduce emissions substantially.

Asked for his reaction to the environmentalists’ seige on his factory, Shahi shrugs and says that it has become fashionable to blame Himal Cement for all ills without scientific proof. “Fog gets called smong here,” he says,.’ “for whole days the when our kilns are closed down, the air quality remains the same, how do you acount for that? I would welcome who ever wants to come and check the factory’s emissions”.

Shahi’s figures do not tally with those produced by Batu Krishna Upreti, of HMG’s Environment Impact Study Project of HMG, who writes that Himal Cement’s emissions before the factory’s recent expansion were 4,5 grams per cubic metre. By comparison, the emission limits for similar factories in, West Germany and India are 120 mg and 250 mg per cubic metre. About 400 tons of dust could be prevented from being spewed into the Valley atmosphere every year if’emissions were controlled, says Upreti.

■ Upreti also states that the factory’s dust has affected the health of its workers as well as those in surrounding villages. Mana Man Singh, 67, a life-long resident of Chobar village high on the ridge above the factory says he and his neighbours often reflect on how their lives have changed since the factory started. “Depending on the wind conditions, our village and Sanga village across the Bagmati are enveloped in dust – dust on our fields, our beds, our kitchen, everywhere. We cough and suffer. What to do? The factory gives many of the villagers employment. My two sons as well”. Singh’s former house and gardens were long ago swallowed by the factory’s excavations. He has been moved .once after that and yet another move is threatened, to satisfy the factory’s (and the country’s) every increasing appetite for cement.

Hinial Cement’s silica dust, ash and smoke do not remain restricted to the immediate .environs and villages, but Spread in a thin haze throughout the Valley, taking the shine off temple roofs and sometimes making the nearby Himalayan peaks nothing but vague white apparitions. Suresh Chalisey, who lias observed Chobar’s smoke with a professional and despairing eye for several years, says there is a “gully effect” that keeps the haze from dispersing. He says that in the forenoon period, the wind in Chobar blows east, turns westerly in the early afternoon, and becomes northerly later in the day. “Rarely does it blow south and away from the urban centre”, he says. “East or west, the smoke and dust hug the base of the hills from Godavari to Swayambhu, then diffuse through the rest of the Valley”. The local weather patterns make Kathmaodu doubly vulnerable to air pollutants, says Chalisey.

While Chobar might be one of the primary air pollutants in the Valley, exclusive focus on it has led to the neglect of other sources. Such as the two Chinese-built brick and tile factories and some hundred odd brick kiln chimneys that dot the landscape in Harisiddhi, Bafal and elsewhere. The kilns Use coal and firewood and are a significant source of smoke pollution.Domestic use of firewood also remains one of the main traditional causes of air pollution.

Vehicles are adding to the foul air. Their number has quadrupled over the past decade, and there are 2,000 more cars, buses, trucks, autorickshaws, tractors and power tillers every year for the next decade. In February 1087,13,460 cars and jeeps were registered in Kathmandu; and 6,150 motorcycles 4,510 buses, trucks and minibuses 900 power tillers and tractors and 620 autorickshwas. That makes a total of 25,640 internal combustion engines (though not all of them might be on the roads), many of them badly maintained so that they emit more carbon, sulphur and lead. The quality of gasoline and diesel that enters Nepal makes these vehicles even more prone to pollute, say experts.

‘To minimise pollution, fuel should be free of lead and should contain as little sulphur as possible”, says Guna Raj Upadhaya, Executive Chairman of Nepal Oil Corporation, “We do not have a Nepali standard, so we follow the Indian standards for diesel and gasoline. Nepali fuels contain less than one per cent sulphur.” That point is borne out by a study done by Diesel Kiki, a Japanese company, for Sajha Yatayat. It reported that the sulphur content of Nepali diesel was “lower and better than Japanese diesel fuel”.

However, the carbon content of diesel in Nepal is high because the Barauni refinery in Bihar which processes the fuel has old equipment that leaves a high wax content. Diesel Kiki reported that the carbon residue by weight in Nepali diesel was 2 percent, while in Japanese diesel it was a mere .01 percent – which makes Nepali trucks two hundred times more prone to belch smoke. Which they do. Especially notorious are the hundreds of mini-buses sold by overland tourists to Kathmandu transporters. Badly maintained diesel engines, with defective pumps.and fuel filters, fail to propoerly ignite the fuel and leave smoke trails of carbon all over the Valley.

Nepali cars, autorikshaws and other gasoline users are also more liable to pollute, because of low octane and high lead content. Lead-free gasoline is unheard of withjn the kingdom. Fuel with high octane rating allows thorough combustion so that there is little carbon exhaust. Unfortunately, while2.93octane value gasoline does come into Nepal, only 1.87 ocatane value gasoline is available for general use.

“Carbon in the atmosphere, such as comes with Kathmandu traffic during office hours, weaken the lungs and lead to inflammation and infection”, says Dr. Purushottam Shrestha, Professor of Community Medicine at the Teaching Hospital. He feels that planners must learn from the mistakes of other cities before pollution become unmanageable in the Valley. Over at the Planning Commission, Upendra Man Malla says that while there is an environmental and land use policy spelt out in Nepal’s current Seventh Five Year Plan, it has not yet been put into practice. However, there is no specific legislation for the regulation of pollution. “We cannot just wait for everything to clog up before doing something”, he says.

Traditional “organic pollution” on the streams and streets as well as the more recent “industrial pollution” from factory and vehicles have brought Kathmandu Valley to the crossroads and a choice has to be made between environmental chaos and public health. The latter kind requires the government to set and enforce pollution standards on industry. It must also attempt to control the number of vehicles and begin a process of checking their emissions. The traditional variety of pollution, which always existed but has recently become more pronounced, requires a change in habits and attitudes.

Prakash Khanal is a Kathmandu-based journalist snd photographer who specialises in science reporting. Anil Chitrakar is studying irtdustiial engineering in Jaipur and helped found the TREES environmentalist group in the Valley.