From Nepali Times, ISSUE #262 (26 AUG 2005 – 01 SEPT 2005)

Muted coverage of the assassination shows how far we have yet to go to attain true regionalism

The minimalist manner in which Southasia as a whole greeted the assassination of Lakshman Kadirgamar at age 73 indicates the failure of regionalism.

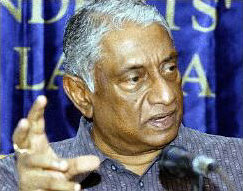

The Sri Lankan foreign minister, killed by a sniper close to midnight on 12 August, was a towering regional figure whether you liked his politics or not. A Tamil Christian from Jaffna who actively sought to discredit the Tamil Tigers and thereby earned the undying enemity of one of the most vicious militancies in the world, Kadirgamar was courageous and steadfast in his chosen mission. He represented the old-world colonial-era graciousness that Sri Lanka retains more than any other former colonies and was a notable orator who as recently as March of this year had been feted by his alma mater, Oxford University. The last time most of us saw and heard him was during a prickly discussion on the BBC’s HardTalk program that same month.

The muted response to the assassination is evident from the newspaper headlines. Granted, editors all over were caught unawares because the killing happened when most of them were closing their pages. By the time news arrived from the wire services, it was too late to give a banner headline for the papers of the 13th. Nevertheless, one could have used bold black headlines instead of the small items tucked on the side, if at all.

By the 14th, the story was too old in this age of 24-hour television news to make the front page leader. The only exception was The Hindu of Madras, the Indian newspaper that is most interested in what is happening across the Palk Strait. For most papers in the rest of India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan, follow-up on the Kadirgamar assassination joined the inside ‘international’ section.

The media indifference seemed to go beyond the press and television editorial sections. One really had to look around for discussions organised in the wake of an event which threatened to take Sri Lanka back to the edge of societal disaster. What impact would the assassination have on the fragile ceasefire between the government and the LTTE? Who killed the foreign minister and for what purpose? Was it the LTTE or some of its rogue cadres? Was it disgruntled elements within the Sri Lankan Army? Was it the JVP? Not enough people in Southasia outside Sri Lanka cared to seek answers and interest was limited to signatures on forlorn condolence books kept at the Sri Lankan embassies.

Kadirgamar was a key player in the Sri Lankan conflict, principal aide to President Chandrika Kumaratunga and controversial as anyone in his position would be. Sri Lanka has seen two decades of continuous violence that has pushed itself into the headlines and newscasts year after year after year. If there is one conflict that Southasians know beyond Kashmir due to continous coverage of carnage it is this conflict.

The passing of Kadirgamar might as well have been an assassination of an obscure politician in a faraway African or Latin American country for the kind of interest it generated in the media and intelligentsia in the region. This indicates the inadequacy of Southasian consciousness amongst even the English-speaking and reading classes of the countries of the region. Obviously, there is some distance yet to be travelled before empathy develops for the neighbour.

It could be that the lack of interest across borders is because the lives of our peoples are not intertwined either by politics or economics. Empathy which will ultimately bring Southasia together has yet to develop. The mild reaction to the killing of Kadirgamar shows there is some distance to travel yet on the road to Southasian regionalism. A sobering thought as SAARC prepares for its rescheduled summit in Dhaka in November. Lakshman Kadirgamar will not be there.