From HIMAL, Volume 0, Issue 0 (MAY 1987)

The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) has completed two years of operation and “is off and running”, according to its Director, Colin Rosser. The difficult ground-breaking activity is complete, he says, and the Centre is already into the “second phase” of its existence, carrying out substantive activities which will benefit the mountain people of the Hindu-Kush Himalaya and elsewhere.

Although the Centre’s work so far is appreciated, however, the course has not been set and locked. Within ICIMOD and among observers there is debate and also an undercurrent of unease as to what it is and what it should do.

“We started with a handicap right away because too much was expected of us, especially at our base here in Nepal”, says a senior staff member. There are other, perhaps more serious constraints — regional politics, limited finances and the inability to attract recognised names from outside the region because of low pay scales (by international standards). Regionally, ICIMOD has not been able to reach out to three countries named in its statutes — to Afghanistan. Bangladesh and Burma — though it is not for want of trying.

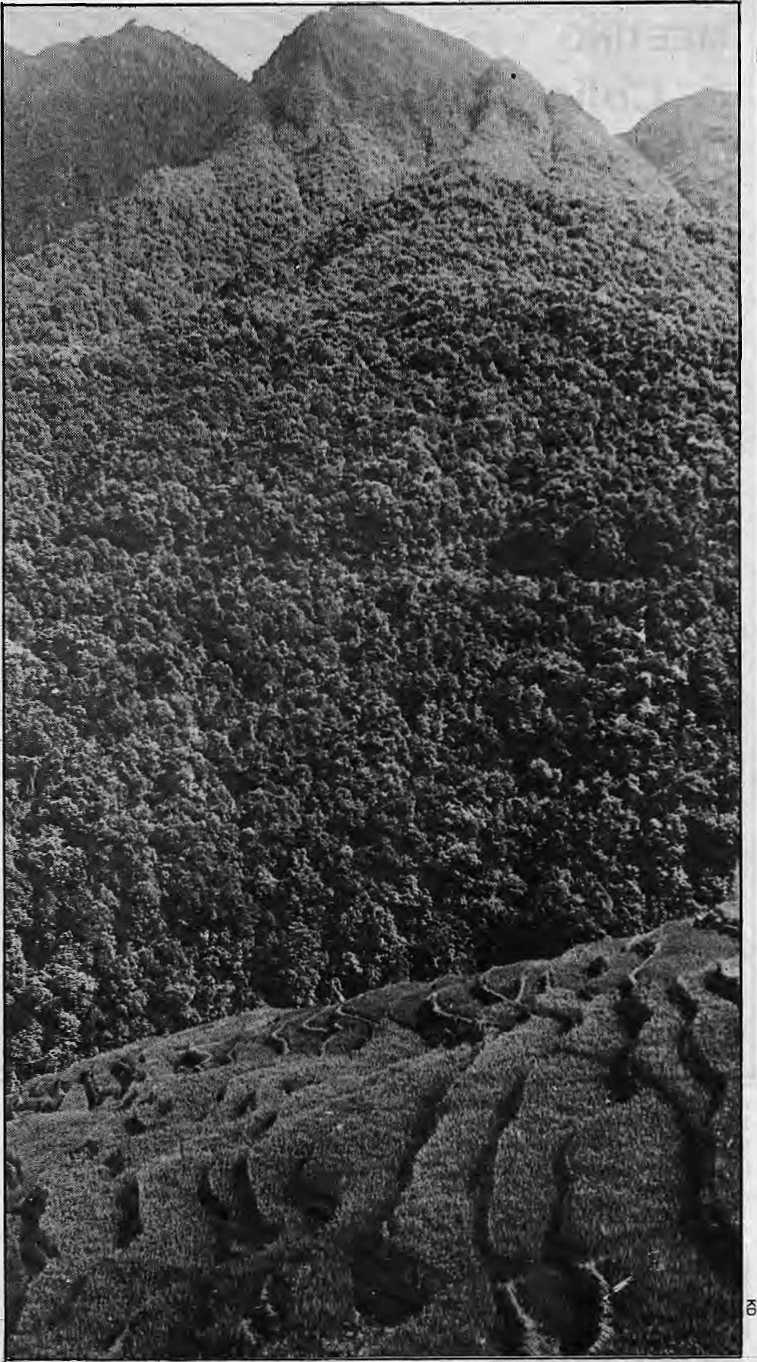

symbiosis in the mountains

ICIMOD was inaugurated at the culmination of a week-long symposium in December 1983, attended by international luminaries such as UNESCO’s embattled chief Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow and Maurice Strong, Canada’s environment and development pundit. The Centre was established to benefit the hill farming community of the Himalaya Hindu Kush and elsewhere, one of the most neglected segments of the world’s population. It was decided then that the first couple of years after starting operations in September 1984 should be a period of stock-taking, and institution building.

During the time, ICIMOD had assembled a gifted staff of 25 from the region, set up shop in a “campus” of seven buildings in Patan, organised five major international workshops (on watershed management, rural energy,”rural-urban linkages”, off-farm employment and national parks), begun collaboration with other agencies, awarded its first Senior Research Fellowship (US$25,000 to Nepali botanist Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha), and established a computerised documentation centre.

“International”: As a centre for study and research, ICIMOD should not have to worry about political problems related, say, where to hold a conference or seminar or whether Gilgit or some other locality is actually in India, Pakistan or China. But in a region rife with burning suspicions and simmering border disputes, it would be naive to think that ICIMOD could proceed with political blinders. Looking at it positively, however, ICIMOD is the one regional centre where experts from antagonistic neighbours can interact on a daily basis in an atmosphere of professional cordiality. “If nothing else, that in itself is an achievement, though perhaps an inadvertent one,” says a Nepali Foreign Ministry official with knowledge of the Centre’s functioning.

While its character is “international”, the Centre’s mandate is limited to improving the living standards of the populations in the eight countries of the region from Afghanistan to Burma. While ICIMOD has already set an impressive record of international liasons, its ability to impact on other mountain systems is restricted by funding. The Centre’s annual operating budget, of US$1.5 million plus half a million in special programmes, is comparatively small. A similarly situated organisation, the International Institute for the Management of Irrigation in Colombo has a budget of US$5 million.

ICIMOD’s ambition to be a “centre of excellence” requires an ability to hire the best expertise available and to go out of the region to recruit, if necessary. Because the ICIMOD member states were wary about giving United Nations salaries in a centre headquartered within the region (Nepal and India wanted to lower the pay scale, Pakistan to up it, and China thought the whole idea was ridiculous), ICIMOD finds it cannot compete in the world market for permanent professional staff. The 1981 salary scale of the Asian Institute of Technolgy in Bangkok was taken as a benchmark and ICIMOD’s own scale locked to it. By paying short-term contract holders at slightly higher daily rates, the Centre is, however, able to attract international expertise, albeit for shorter stays.

“Centre”: A staffer confesses, “It is not yet clear whether we are to be a think tank that will operate out of an isolated ivory tower, or an implementing agency that will compete with all the Other agencies, international NGOs and government departments.” A few think that ICIMOD must “aim for the masses”, and try to bring the “fruits of development” directly to the farmer on the terrace. This last proposal is largely rejected, firstly because of the enormous political difficulties that it would entail. However, there continues debate among those who feel that there must be some applied field programmes. Others would go halfway and get involved with actual projects, but at the planning and monitoring stages only.

“Integration”: Debate also continues as to how best to achieve “integrated mountain development,” whether ICIMOD itself should conducted integrated research or merely espouse the proper management of sectoral programmes. J. R. Dunsmore, of the British Overseas Development Administration, had asked back at the 1983 symposium, “To what extent do we need to aim for integration of the implementation programme except in the natural resource field?” The point was whether, having once assessed the whole range of resources of an area and decided on a programme for their development, whether there was an over-riding advantage in having an integrated mode of implementation as opposed to a multi-sectoral approach.

Another criticism, from within ICIMOD, is that it boasts of a “multi-disciplinary team with sectoral attitudes” that people trained sectorally are finding it hard to talk about integrated mountain development. Further, it is said, as ICIMOD is not an implementing agency, how is it going to prove the workability of the integrated concept?

Duplicate work

“Mountain Development”: If it is not to duplicate work conducted elsewhere, some say, ICIMOD must quickly make up its mind about what issues constitute mountain-specific development, as against of “general development”, which could apply just as well to island eco-systems, the desert, the African savannah and the Indo-Gangetic plain. It is also unclear how the mountains can be completely isolated from the plains and how the “highland-lowland interactive system” can be ignored.

An observer says, “First the centre must clearly identify its primary clientele, whether they are the policy making governments, the operational line agencies, the mid-level professionals or the public at large. The region is so poor, and the intellectual pool so limited that it must get a clear focus on the mountain dimension of the work to be effective.”

Geographer Harka Gurung, known for his forthrightness, believes ICIMOD has started on the right foot by providing an increasingly effective forum for regional development and environmental issues. His chief grouse is that ICIMOD has yet to define what the “Hinmalaya Hindu Kush is, where it ends and where it begins, what are its geographical components.”

Gurung continues, “ICIMOD still lacks a framework. If you want to be problem-oriented, you have to define the space, and ICIMOD’s fundamental scientific base is unclear. The second stage of its work must be a synthesis of what it has learnt, and that requires homework.”

Homework

Much of the homework will have to be done by Director Colin Rosser, who is due to retire in mid-1988 and wants to leave his successor with a Centre that has both excellent output and focus. He has a challenging task confronting a welter of conficting demands and interpretations and emerging with an answer that must carry, ICIMOD will into its first decade (see interview). To help find ICIMOD’s soul, Rosser is calling together its international Board of Governors, together with several prominent names in international development and mountain environment, for a brainstorming session in May 11.

MEETING

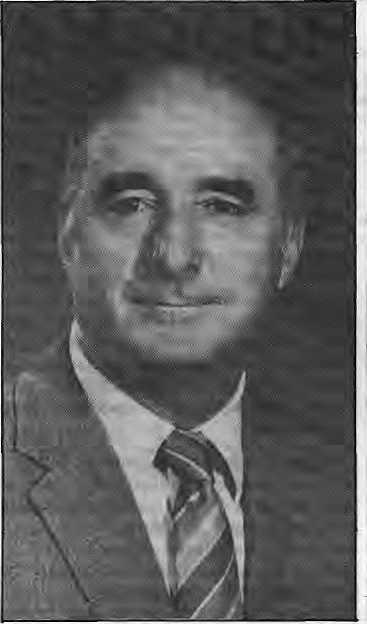

Colin Rosser: “We’re Off and Running”

Colin Rosser, 62, a sociologist who did research among the Newars east of Kathmandu valley more than two decades ago, is also a former British Gurkha officer with experience in India and Pakistan. In 1984, he was appointed the first chief of ICIMOD and his term expires in mid-1988. Rosser spoke on where the Centre is and where it is headed to HIMAL Editor, Kanak Mani Dixit.

HIMAL: After more than two years at the helm, do you feel ICIMOD now has a grip on what is its calling?

Colin Rosser: Let me first explain ICIMOD’s pedigree as a “third generation” international institute. First, you had institutes with a global focus like IRRI in the Philippines, which applied science to a particular discipline. When it was realised that the social sciences could not be ignored in propagating scientific advances, a second cluster of institutes were born, such as those dealing with irrigation and agro-forestry in Colombo and Nairobi. ICIMOD represents a further step, the first institute of its type, which studies the integrated development of a total eco-system. The Centre’s establishment brought together the ecologists worried about mountain degradation and scientists seeking to bring about development through agriculture.

HIMAL: Do you emphasise environment or development?

Rosser: Priority must be given to development and not the enironment, especially if you see environmental activities as part of a holistic development process. I want to get away from words like “crisis”, “doom” and the whole catalogue. Rather than espouse crisis-laden scenarios, the Centre will focus on development efforts, taking full account of scientific advances.

HIMAL: Does ICIMOD hope to reach out of the region and become more “international”?

Rosser: The Himalaya Hindu Kush has been written into our statute. However, we do hope to make use of the available knowledge in the Andes, the Alps and the mountains of North America so as to better understand the problems of the Himalaya. There is scope for cooperation in the area of mountain crop genetics, for example. For the moment, we are a reception centre for knowledge, but in time we hope to be a transmitting centre as well.

HIMAL: Where is the organisation headed institutionally?

Rosser: As I said, we are currently trying to become an efficient clearing house of information, looking for success stories in the mountains and propagating them. At present, one valley does not know what is happening in the next. The loss of acquired knowledge in these mountains is collosal! People learn and forget before others have an opportunity to benefit from their experience. We want to help preserve practical knowledge — for example, the insights of an engineer engaged for ten years with the Lamosangu-Jiri road, which you will find in no engineering manual.

We would like to do original research, but that requires a budget of US$ 5 million, as against our present spending of US$ 1.5 million. If we were to assist in opening up centres in the other major mountain systems, that would be US$ 10 million. Of course, we’re nowhere that right now.

HIMAL: So ICIMOD is going to limit itself to information transfers?

Rosser: Oh, no, that’s only the first step. We plan to train professionals: foresters, engineers, planners and others. Even those with degrees earned abroad are on the whole pretty poorly trained. In our second phase of work, which has already begun, we are building up a bank of case studies with which we hope to “irrigate” existing training programmes. This year, we will have case studies ready on watershed and forest management, pasture and fodder use, organisation of rural development and districtlevel energy planning.

We are also engaged in “action research” for formulating a project on rural-urban linkages as it relates to Kathmandu’s produce market. In order to increase urban access of farmers, we hope to identify the points in the commercial chain where private sector, public sector or external aid investment can be used to maximum advantage.

HIMAL: How about implementing development projects on your own?

Rosser: With our miniscule budget, we can only hope to act as catalytic agents. The annual public investment in the Himalaya mountains is US$ 1 billion, so the problem is not one of money. We do not want to add to existing projects, but we would like to add to their quality. “Why can’t we get good projects!” is the constant refrain of the donor agencies. We will design and monitor projects. As a think tank, however, we can only advocate, argue and present the case.

HIMAL: Are you in touch with other institutions in the Himalaya?

Rosser: Clearly, we have a coordinating function. There are already over a hundred universities, research institutes and field stations all concerned with mountain development in the region. The work of many of them overlap, for example there is incredible duplication in soil erosion research. Our seminars, symposia and publications help promote more efficient use of the available financial and intellectual resources. There is camaraderie among professionals in the field, regardless and a willingness to collaborate.

HIMAL: Who are ICIMOD’s end-users?

Rosser: The final beneficiary, of course, is the hill farming community, but we do not address them directly. We hope to gain the understanding of professionals such as economists, administrators, officials, journalists and teachers.

HIMAL: The Centre’s departments are divided sectorally, so how do you achieve “integrated development”?

Rosser: The problems on the ground are integrated — the farmer does not sectorally divide his worries. As long as we remain engaged with real problems on the ground, and focus on “total development”, I feel that ICIMOD will have fulfilled its mandate.

HIMAL: There must be political constraints to your job.

Rosser: The Himalaya Hindu Kush is a politically sensitive region. In dealing with social and economic aspects of development, as we do, one is talking about policies, and policies cannot be separated from politics. So there is a problem here. A centre in a region with a history of wars and continuing boundary disputes has to be constructed with unusual diplomatic skill — so that work can proceed on agreed priorities.

HIMAL: It seems you have been unable to convince all the countries in the region to get involved in ICIMOD.

Rosser: Burma, as you know, has always remained aloof from international and regional groupings and we have not been able to open its door any more than others. Afghanistan did attend our inaugural symposia in 1983, and we hope that it will become more active when peace finally arrives. Bangladesh maintains that it is not a mountain country, but we have been trying to emphasise the importance of the mountain-plains connection.

HIMAL: ICIMOD’s salary is the talk of the town.

Rosser: It is true, the Centre is very much like a fish out of water in Nepal on that count. But bear in mind that our salaries are somewhat lower than the United Nations standard. But I ask you, should I pay a Nepali any less than a colleague from another country? Further, if our salaries can attract Nepali experts back from lucrative jobs abroad, that can only be good. As far as possible, I want to use the skills of the region.

At ICIMOD, we have as little hierarchy as possible and all staff get their pay without reference to national or regional origin. There is no north-south divide. My colleagues are encouraged to concentrate on their work untramelled by bureaucracy and hierarchy. We have no advisers or consultants. We’re also trying to put Kathmandu on the world’s stage as an international meeting place of repute where an independent, autonomous body such as ours can operate with ease.

HIMAL: Where to now, for ICIMOD?

Rosser: It has been two years, and we’re off and running. Remember, we started with a pedigree, but no model. Today, we’re in the institutional map of the region due to my hardworking, productive colleagues. I am not concerned about ICIMOD next year or the year after, but of what will be its character ten years from now. What is our long term future? To help provide answers, the Board of Governors is holding a brainstorming session starting 11 May, to which we will be inviting persons with recognised excellence both in running international development centres and in the area of mountain development.

In the past couple of years, we have made some mistakes and learnt some lessons. It is now time to stop and ask some fundamental questions.