From Himal Southasian, Volume 11, Number 6 (DEC 1997)

Kathmandu is closer to Beijing than to Lhasa.

Till as late as the first decade of this century, the government in Kathmandu paid tribute to the Chinese court. Once every five years a party would head out of Kathmandu overland across Tibet, bearing gifts, taking three years for the round-trip to Beijing. A practice begun after 1791 when Chinese forces, responding to Tibet´s call for help in what was turning out to be a very one-sided Nepal-Tibet war, reached within a day´s march of Kathmandu before Nepal sued for peace.

China is still extracting tribute from Nepal today, albeit in a slightly different guise. These come in the form of the reiteration of the refrain: “Tibet is a part of China; Nepal will not allow any anti-Chinese activities from its soil; Tibet is a part of China…”

No matter whether it is King Birendra, prime ministers, trade delegations or journalists´ groups who go visiting Beijing, the Chinese never fail to extract this oral tribute, which is mouthed as a matter of course. Needless to say, this does not do much to enhance the Nepali self-image.

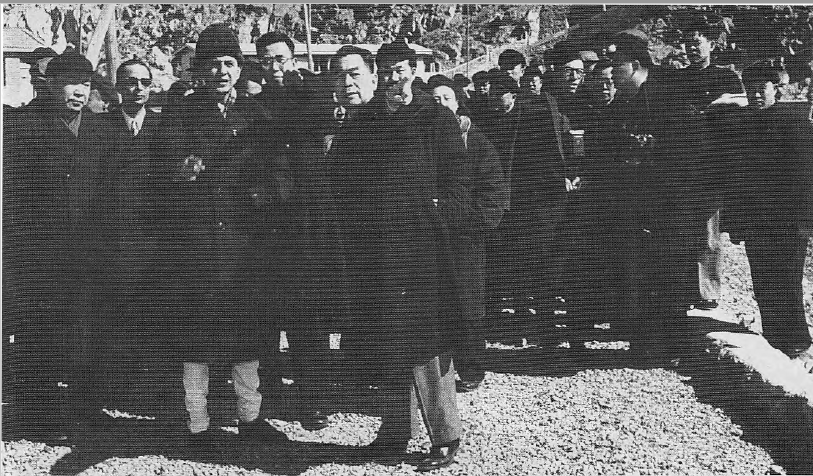

Poor sense of self has of course long afflicted Kathmandu´s foreign policy generally. It is a far cry today from those heady days of the early 1960s when Nepali leaders such as Bishweswor Prasad Koirala, Nepal´s first popularly elected prime minister, stood tall and self-confident, side by side with a Jawaharlal Nehru or a Zhou Enlai. It was back then that Nepal´s China policy was designed, to be sure, taking into consideration the Cold War and the Sino-Indian rivalry. Nepal was having to prove its sovereign status to a sceptical India, and also needed China desperately to balance India´s overwhelming presence in its economic and political life.

But even back then, China had implicitly recognised that Nepal fell within India´s sphere of influence. According to the recently published memoirs of Koirala, B.P. Koirala ko Atmabritanta, 1998, when he had visited China during his brief tenure from 1959 to 1960, Zhou Enlai himself had acknowledged as much. Referring to the volume of Indian aid to Nepal, the Chinese premier had indicated that Beijing´s contribution would have to be slightly less. When Koirala asked why, Zhou replied: “It will not be good either for you or for us… We should not compete with India in providing aid to you.”

Chinese crutch

Times have changed, and Nepal´s own sovereign status is unquestioned. At the same time, the ability to play China and India against each other has diminished considerably (despite the immediate downturn over the course of May 1998). China now has, in so many words, conceded the south of the Himalaya as outside its immediate area of influence and interest.

This in itself need not be a matter to make Nepali policy-makers disconsolate, for it provides an opportunity for smart diplomacy to take the place of an outdated equidistance policy. It should be possible for Nepal to fashion an independent and self-confident regional policy for itself without the need of a Chinese crutch.

As far as Beijing is concerned, meanwhile, the place of Nepal in its scheme of things has diminished considerably over the years and today the importance is only in relation to activities that may be carried out from the south against its presence in Tibet. That, and the activities of Chinese construction companies and contractors in Nepal.

One may, of course, forgive Shital Niwas (the redbrick palace where Nepal´s foreign ministry is housed) for not taking the initiative in defining a more self-confident approach towards China. It is the members of the Nepali intelligentsia and media which show an even greater lack of imagination. Since the diplomatic shackles binding the foreign ministry do not affect them, they could conceivably have taken an independent stance on China and Tibet.

They could, for example, dare speak on matters such as cultural inundation or the Han migration into Kham and Amdo, the matter of religious freedom and human rights, or the socio-economic conditions within Tibet. They could also raise discussion on Tibet´s distinct identity within China, and the quantum of sovereignty that might be appropriate, something that even the Dalai Lama is willing to consider. They could, perhaps, speak up on allowing the Dalai Lama to visit Nepal on a purely religious mission, as is the formula employed elsewhere.

All this is, of course, what the Kathmandu intelligentsia could do. The reality, however, is that any person who raises one of these points is immediately, and contemptibly, tarred as a “Free Tibet wallah”.

(Interestingly enough, B.P Koirala recalls in his just-published memoirs, “…For one thing, because we were socialists we were for Tibet´s independence and we believed that the Chinese action was an aggression… When the talk turned to Tibet, I told jawaharlal Nehru, ´You have given Tibet to China on a silver platter.´ To which he replied, ´So, am I supposed to send an army to put the Dalai Lama on the throne?´ My answer was, ´There is no need to send in the army. But you have given international endorsement to the Chinese action, you have recognised it. And you are also telling us to leave China to do what it will…´”)

When in their bilateral banquet toasts the diplomats drink to the “age-old ties between Nepal and China”, they mean, more than anything else, the historical links of Nepal with Tibet. But the lack of interest of the Nepali educated class towards Tibet over the last half century has accelerated the eclipse of Tibet from the Nepali mind. This, despite the fact that the most popular ballad in the Nepali language continues to be Muma Madan, the tragic tale of a Kathmandu trader who leaves his family to go trade in Lhasa.

Mao badges

Today, Tibet has become so remote that Nepalis do not even know enough to take pride in the fact that much of the great religious high art of Tibet, in bronze or canvas, have their origins in the great cultural outpouring of the Kathmandu Valley. For centuries, Nepali traders supplied Tibet with goods from India and maintained a strong mercantile presence in Lhasa and other towns on the high plateau, to the extent that Nepali coins were standard currency. The cross-border interactions between the ´Tibetan´ regions of northern Nepal and Tibet have naturally been intense.

Much of the cultural, economic as well as cross-border community links were abruptly terminated with the Chinese takeover of 1959. During the Cultural Revolution, Nepal´s hills were flooded with Mao badges, which pushed Kathmandu to counter with King Mahendra badges. For a while in the early-1970s, the Kathmandu government did look the other way as the Central Intelligence Agency, with connivance of Indian agencies, supported Tibetan insurgents in attacking Chinese convoys and installations from bases in Nepal. However, this did not last long; pressured by China, the Nepali army saw its only combat action in this century when it did away with the Tibetan insurgents in 1974.

There is a highway, of course, which links the Tibetan plateau with the Ganga plains through Kathmandu. However, as the route is roundabout, Nepal´s Tarsi has not been able to utilise it fully to supply its surplus agricultural produce to Tibet. A more direct road, planned in 1960, was shelved because of Indian misgivings that such a road would mean direct Chinese military access to the Ganga plains.

The road is finally being built with Japanese aid, as a single-lane feeder road. There is cold comfort in this, however, as a more direct route from Lhasa to the Indian plains is in the offing. The roads are already complete on both sides, taking the Chumbi Valley route from Tibet, and into the Siliguri railhead in the Duars either via the Nathu La or Jelep La passes (in Sikkim and West Bengal´s Darjeeling district, respectively).

Only diplomatic niceties having to do with Chinese lack of formal recognition of Sikkim´s incorporation into India is said to be stopping the border from being opened. When that happens, the trade conduit from Tibet to the sea will open, and Nepal which has been the historical custodian of trade with Tibet will be left out in the cold.

Tibet is a vast storehouse of natural resources, and its economy will rise sooner or later. But because the Nepali government and intelligentsia have forgotten Lhasa, the Nepali links to that city are by now tenuous. The private sector has come up with no initiative to maintain a presence in Tibet´s growing market, nor has the government embarked on any effective economic diplomacy which could mature to the benefit of Nepal in the long run.

Trade with Lhasa

The bulk of the economic advantages of Tibet´s opening will, of course, now be picked up by the Han Chinese whose influx has turned Tibetan demography on its head. What is left over, will be picked up by Marwari and other Indian businessmen who are bound to land up in Lhasa before long, and certainly once the Siliguri-Lhasa route is operational. At best, then, Nepal will remain a transit point for the western high desert of Tibet (or Changtang), rather than the populated and productive eastern regions of Kham and Amdo.

The lack of erudition and imagination which marks Nepal´s foreign policy in so many other areas is also clear and obvious in the case of China/Tibet. The blacking out of Tibet from the Nepali mindset means that, when the time comes, Nepal will lose out to India in taking ´advantage´ of Tibet. The traders in Siliguri are gearing themselves up, while Nepalis stick to the refrain “Tibet is a part of China…”