From Nepali Times, ISSUE #283 (27 January 2006- 2 February 2006)

A film from Peru that steers too close for comfort is being premiered in Nepali

The ‘Barrel of the Gun’ section of the Film South Asia ’05 festival lastOctober showed two documentaries on Peru’s Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) rebellion and the state’s reaction as orchestrated by charismatic, dictatorially inclined president Alberto Fujimori.

One film, The Fall of Fujimori, focussed on the corruption and shamelessness of the president, his downfall and abject and anonymous exile in Japan. The other film was State of Fear, which saw its Asian premiere inKathmandu and is gathering momentum in screening halls in New York City and elsewhere.

No experience of two countries can be exactly alike and societal factors specific to each nation state will define the course towards peace. Nevertheless, State of Fear resonated among the Nepali audience at FSA ’05 because of so many disconcerting parallels. The underlying historical exploitation of the indigenous population vis-à-vis the upper-class white Latinos, the distance between the sheltered capital of Lima and the hinterland,he urban classes looking the other way until the terror arrived at their door-step–and then a willingness to let loose the dogs of war.

Other aspects of the film will make Nepalis nod in recognition: Fujimori’s excuse of the Shining Path terror to destroy democracy; the Lima regime’s attempt at military pacification which terrorises the peasantry of the hills and plains jungles; the brutality of Comrade Gonzalo’s rebels, the Peruvian military’s reliance on torture and disappearances and its impunity; Sendero’s recruitment of child soldiers and indoctrination of Quechua youth; peasants caught between the militants and the military and the arming of village vigilantes by the army.

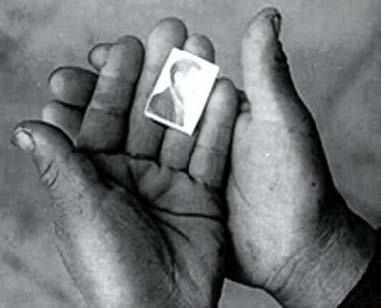

The visual cues are also disconcerting. In places the Andean altiplano resembles eastern Nepal. The build and facial features of the indigenous population reminds one of the ethnic people of Nepal’s hill and plain. We see the same Kazak Mi-18 helicopters landing on tropical ridgelines. Gutted homesteads inPeru look the same as gutted homesteads in Nepal. Fujimori’s destruction of Peruvian democracy was followed by a period of massive corruption and loot by his henchmen and cronies. State of Fear forces us to constantly compare and contrast.

But Peru is not Nepal and there are indeed sharp divergences in experiences across the seven seas. Fujimori never sought a political resolution, instead he captured Gonzalo and displayed the rebel leader in a cage. In Nepal, other than elements in the royal regime, everyone seeks desperately a political settlement. At their top most levels, the Maobadi themselves have conceded to the future multiparty polity. While seeking to address their internal contradictions and worship of violence, the rebels of Nepal are seeking a ‘safe landing’, even as the Kathmandu regime seems to prefer the Fujimori solution.

We in the Himalaya must learn from the Andes. Perhaps we will be saved from going the way of Peru, with State of Fear helping usunderstand the menace of a de-politicised, militarised society. Towards the end, the film emphasises the importance of exhuming the memory of death and destruction, of truth commissions that place accountability for inhumane acts by rebel, soldier and dictator alike. Only then can there be true reconciliation and confidence in the future. This is ‘transitional justice’. Societies will not emerge undamaged from dreadful episodes unless we uncover the truth: what happened and who did what. Nepalis will need to go through this exercise and not paper over the past. We too will need a truth commission.

The learning from State of Fear would have been limited to a privileged Kathmandu audience if it had shown only at FSA ’05. But a group of volunteers has with the permission from the film’s producers (Skylight Pictures) translated and dubbed the film in Nepali. Bhayako Rajya will premiere in open exhibition at the Ashok Hall in Patan Dhoka at 1PM on Sunday 29 January. Tickets available at the gate.