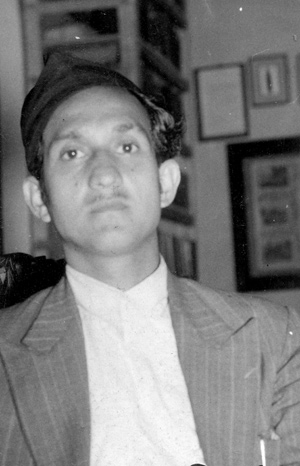

The Rising Nepal (Jan 11 1979) Courtesy MPP Archive

We have to talk of Kalanath Adhikari in the past tense. Though Kalanath the man is yet very much alive, Kalanath the unequalled songster has now been pushed away from the lime-light, sent on his way by a large measure of underserved public apathy. Today, things have come to such a pass that even those of us who are past the age of forty will be hard put to recollect his name and fame. As for the younger generation, it does not know him from Adam. Kalanath who, they are liable to ask.

Kalanath Adhikari, as a popular singer, hit his peak somewhere around the early nineteen fifties. Then he let his grip slacken, and by 1965, the name had already been partly erased from public memory. And now, a quarter of a century later, it seems as if Kalanath had never even existed. With the passing years piling up one over the other, it is already very difficult to try and gauge what place Kalanath held in public esteem. So we will have to make an excavation back through the sedimentation of time, and recover in a small way the aura that has faded.

In the very short history of modern Nepali music, Kalanath Adhikari acted as a vanguard, laying the basic foundation for the “modern Nepali song”. While his contemporaries like Ratna Das and Govinda Lal stuck to modern Indian prototypes, Kalanath was the first to include a distinct Nepali flavour into modern songs. He was to be equalled in a neighbouring field, only by Dharma Raj Thapa, who mostly sang embroidered folk music.

While Dharma Raj made his niche in folk variety, Kalanath stuck to social and political themes, and his songs are like a barometer to the turbulent times of the early fifties. He is perhaps the only Nepali vocalist who wrote his own lyrics, composed his own music for each and every one of the compositions he sang. Musically speaking, the songs of Kalanath were not so melodious, or pleasing to the ear, as are the songs of Narayan Gopal or Aruna Lama today. But even then there was a sort of urgency in his compositions that went through loud and clear into one’s consciousness.

Apart from his music, Kalanath made a significant mark as a poet. One strains for every single word in Kalanath’s songs because he is a singer with a message. In the annals of Nepali musical history Kalanath was one of the very few singers who was really committed. He sang to get a message across. Most of our modern-day crooners love to whisper sweet nothings into the ear of the populace. They moan forth with the sentimental outpouring of love, or in the alternative they will sing compositions dipped with a surface veneer of patriotism. Of such songs, we remember only the music, which can be very good at times. But not much importance is ascribed to the wording in the songs. With the songs of Kalanath, however the things he had to say in whatever context come back and linger in your memory.

Patriotic songs as sung by Kalanath had real depth. Written in the first flush of victory after the Rana overthrow these songs burst forth with the overriding optimism that was the classic hallmark of those days. You do not become patriotic by merely spouting truisms; instead Kalanath led us through a different path till the listener felt love of country boiling in his blood.

Other compositions of Kalanath dealt with more poignant themes like the hardships of rural Nepal, exploitation of women, the nostalgic Gorkhali in Malaya or the cruel grasp of the moneylender. At other times his lyrics bloomed forth with light-hearted sentiments that made the audience euphoric with a sense of wellbeing. Kalanath sang for the man on the gulli and he sang in true Nepali without needlessly Sanskritizing his texts. He made abundant use of onomatopoeia, utilizing this very rich aspect of the Nepali language.

Kalanath proved his versatility by singing the most popular Nepali lullabye yet sung, “Ayeeja Nidari Chunumunu”. This song also proved his sound sense of perspective. He filled up this lullabye with all sorts of wild ideas that could act as a booster rocket to a child’s imagination. He sang of Dharara, Sagarmatha, pustakari and oolinkaths. The connections and juxtapositions that he drew between these diverse tidbits were very delightful.

In a different plane, Kalanath Adhikari gave a metaphysical bent to some his songs. He sang of zero existentialism, and often left unanswered question hanging in the air. The third-worldly flavour invested in two of his songs “Kini Bajcha Murali”, and “Yo Jaldo Filingo” were classics that tried to explore the inner labyrinths of the human mind.

And now, twenty years later, where is Kalanath Adhikari? One thing is certain: that he has disappeared from public view. Radio Nepal is the monopoly medium through which music reaches the nation, and the station has not broadcast a single cut by Kalanath, for the better part of a decade. But how can one complain, when even the later creations of Dharma Raj Thapa are by and large forgotten, because they are not played over the air?

Today, Kalanath is in his mid-fifties. At a time when he should be basking in the afterglow of success, he has been pushed into an obscure corner of the nation’s memory. For a while Kalanath had dabbled in politics, and he even became a labour leader, during which time he developed a village called ‘Shrum Nagar”. He now runs a tiny hotel next to the highway intersection at Pathlaiya near Hetauda. The hotel dormitory is dark and dingy. In summer you have mosquitoes for company and bedbugs for the rest of the year.

Playlist of Kalanath Adhikari Songs: