From Himal Southasian, Volume 21, Number 3 (MAR 2008)

For decades, the national anthem of Nepal was of the kind that made citizens cringe. “Sri maan gambhir…” sung to a Western martial tune that had nothing in common with the Southasian folk or classical traditions. Against a backdrop of Western instruments, it sang praises of the incumbent king, wished him eternal enhancement of status, and hoped that the population would expand hither and yon. The average Nepali was always envious of the Indian anthem, for the fine lilt of “Jana Gana Mana”, the words and music defined by the great bard of Bengal (no matter that it was originally a paean to George V, to welcome him to Calcutta on 27 December 1911).

The recent misadventures of the autocrat Gyanendra – 12th in line after the unifier/conqueror Prithvi Narayan, who created the oldest nation state of Southasia nearly two and half centuries ago – irrevocably destroyed the kingship’s image among the people of Nepal. It also made the old national anthem suddenly and thankfully irrelevant. And that, finally, was how an embarrassing, uninspiring tune and text, which had been a burden throughout Nepal’s modern era, was definitively hurled out the window.

Amidst the political turbulence since the People’s Movement of April 2006, while the polity was busy adjusting to the Maoists in government and addressing a series of identity-led agitations, a competition was held to draft a new national anthem. The lyrics eventually selected were that of Byakul Maila, a man of hill ethnicity (Rai), in a society in which acts of literary creativity have tended to be the monopoly of the caste groups. An allegation that the lyricist had had some form of cohabitation with the former royal Panchayat regime did the rounds for a little while, but in the end was evidently allegedly forgiven – after all, there are few in Nepal could not be tarred in this way if required.

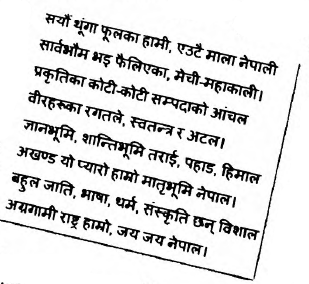

“Saya thunga phulka haami”… the lyrics of the new Nepali national anthem speak of the country being a bouquet of a hundred varieties of flowers, in plains, hill and mountain; with multiple cultures, tongues and faiths; an ‘advancing nation’ made possible by the blood of ancestors, and so on and so forth. The wordings are adequate, if a touch prosaic, but regardless are a welcome release from the stupefying lyrics of the old anthem – though the allusion to ‘blood’ in the new lyrics, which refers to a heroic rendition of Nepali history, with its underlying indication of conquest and subjugation, will be jarring for some, including me. But the music is dramatically uplifting, composed by the living icon Amber Gurung, the great musical impresario who came to Kathmandu from Darjeeling during the early 1960s at the invitation of King Mahendra.

Amber Gurung, with a unique hold over Western classical, Hindostani classical and Nepali folk music, has been a pillar in the terrain of nepali adhunik (modern Nepali popular music), where his expert hand mixes harmony and melody to deliver something quintessentially ‘hill Nepali’ – depending, of course, on how you define ‘Nepali’ in the modern, evolving context.

You could say that the plains of the Madhes-Tarai, as well as the high Himalaya, are not adequately represented in the instrumentation, wording and melody of the new anthem. But granting that possible lacunae, and adding the subjectivity of one person’s appreciation, the music of “Saya thunga phulka haami” (“Made up of a hundred varieties of flowers”) is uplifting, energising and can perhaps be thought of as offering some added energy to our “advancing nation” (agra gaami rashtra hamro).

While most people who listen to the song in its single current rendering* tend to stop and enjoy the tune, curiously it is not being played nearly as often as one would expect – on radio and television broadcasts, school assemblies and so on. The explanation can probably be found in the current transient phase through which the Nepali polity is passing, a period of asserting a spectrum of identities against the recent statist pressures of creating a unified state with a unitary character (“One language, one dress, one identity”). Amidst the agitated atmosphere currently prevailing, in particular the assertion of the Tarai-Madhesi plains and the ethnic-indigenous disquiet, it is understandable that the new national anthem has yet to become a nationwide rallying cry.

And that is appropriate for the moment. But as time goes on and the issues of rights and identity are addressed to satisfaction, it is certain that the words of Byakul Maila and the music of Amber Gurung will catch the imagination of Nepali citizens of mountain, hill and plain. In the meantime, the citizens of Nepal, and those elsewhere in Southasia, may want to enjoy “Saya thunga phulka haami” simply as a song, even if not yet as a national anthem. That could offer some pleasant relaxation as Nepal’s nation-building progresses, with preparations for elections and the continuing work towards the drafting of a new constitution…